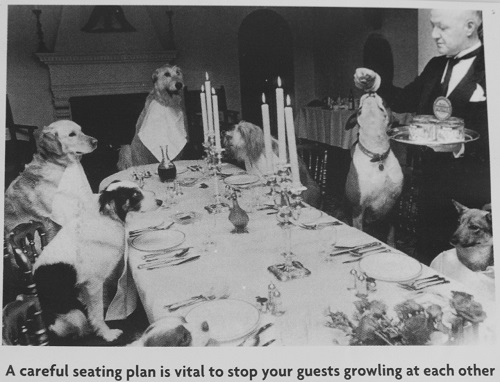

This post may not be wildly relevant to everyone, but it has a wider application: we all find ourselves introducing mutual friends from time to time, and often with a certain amount of anxiety. Will they like each other? Will they each make an effort to be friendly and find some commonality of interests? These are all things that a hostess needs to take into account when seating a dinner party.

There is protocol in every dinner. It may not be official government protocol, as in “Does an Under Secretary of Agriculture outrank an Assistant Secretary of State, and therefore rate a better seat?” but it is protocol nonetheless. The protocol in every dinner revolves around the host and hostess – whomever they esteem most highly sits beside them. It’s a mark of favor, and believe me, people pay attention to this. I’ve known Washingtonians who’ve held grudges for years because they felt they were seated below their rank at a dinner. And if you don’t think an Under Secretary of Agriculture knows that he outranks an Assistant Secretary of State and won’t mind if he’s not seated accordingly, think again.

Seating a dinner is like matchmaking. You want to introduce people who don’t know each other, but who may have similar interests or backgrounds. You want to mix up people of various ages and ranks. There’s nothing worse than a hostess seating all the most prominent people in the room at one table, and leaving everyone else (including the prominent people’s spouses) at a virtual kiddie table. Spouses should always be treated as if they have the same rank as their VIP husband or wife.

There are two kinds of people you should always be sure to include at a dinner party to obtain a good seating plan – the tolerant and the charming. A tolerant dinner guest is a popular and precious commodity. These are the good sports, the ones who won’t mind sitting next to the deaf old lady and repeating themselves all evening, or who can ignore the boors who talk about nothing but themselves all night. They don’t rise to the bait when another dinner guest says something politically inflammatory, but gazes upon them with sadness, as if they can only pity the social ineptitude of such a remark.

Charming guests are also at a premium, especially in the anonymity of a thousand-person charity dinner. These are the people who engage the others at their table and create a “we’re all in this miserable night together, but we’re going to have fun anyway” mentality. (This is where my husband shines, rallying his table with whispered zingers throughout the interminable speeches.) The charming guest is also the person you put next to the Very Busy and Important Person who can’t imagine why they’ve been dragged to this dreadful party full of people they don’t know. The charmer smoothes, they flatter, they amuse, and soon the VIP is putty in their hands.

Successfully seating a dinner comes down to the host’s knowledge of the guests, just as successfully introducing two friends is a matter of knowing people well enough to find others they will enjoy. You don’t seat ex-spouses together, or bitter political rivals, or two people who refuse to make an effort to be social (sometimes you can’t avoid inviting those types if they’re married to someone you really like). Being a good dinner guest is about making an effort, and entering into the spirit of the evening with an open mind and a desire to have fun. Then it won’t matter where you’re seated, or with whom.